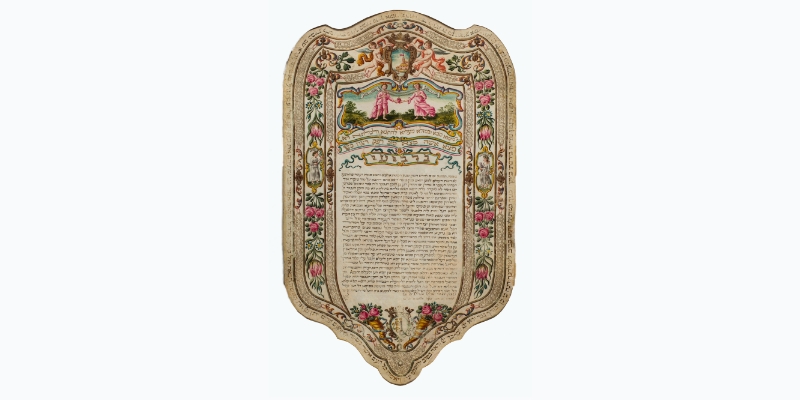

In the course of the eighteenth century, Roman ketubot reached the height of their artistic efflorescence. It was in this period that local folk artists invested great efforts to create attractive ketubot, which are marked by their own characteristic style and distinctive selection of motifs. The result is that they are readily identifiable and resemble no other Italian ketubot. Moreover, while the “Venetian Style” of ketubah ornamentation, for example, was promoted almost aggressively throughout the Veneto and subsequently other parts of Italy, Roman-Jewish craftsmen and their patrons were content and proud with their own specific way of ketubah making. Furthermore, these distinctive features were basically repeated one decade after the other, and, judging from the dowry amounts, popular even among the middle class and less well-to-do families.

As in the preceding period, the bottom border is invariably cut into an inverted or pointed arch, and the narrow text column is surrounded by a wide border, often densely filled with blessings, typically at times shaped into delicate micrographic designs of one or more of the Five Scrolls, and colorful decorations – mostly floral and figural. While many contracts exhibit bouquets of flowers and other floral and vegetal designs, which perfectly fit the joyous and festive event of the wedding, a few other themes, which feature human figures, including at times female nudity, with no inhibition, caught up and became more and more popular in the period that concern us: biblical scenes and personified allegorical figures. Surprisingly enough, to these categories join a third, although a bit less common – mythological figures and scenes. While the biblical scenes are expected, the decoration of a Jewish marriage contract with allegories inspired by Christian art and themes from the ancient Greco-Roman mythology is indeed surprising.

The manner in which the allegories have been depicted in Rome – embodied in young female figures, dressed in elegant attire, and at times even partially or completely nude – is specific to the Roman Jewry with no parallels elsewhere. In asking how and why this came to be, one may point at the Papal capital as the foremost center in Europe of Catholic art in this period. It was already in the Council of Trent that church leaders recommended that religious works of art be simple, clear, and display realistic and intelligible interpretation of spiritual concepts. Allegorical representations with their set and recognizable attributes fit this recommendation well. As a result, an ever-growing literature on the topic appeared in Italy and elsewhere in Europe. The patrons and makers of the ketubot in the Papal capital embraced the world of basically non-Jewish imagery, carefully selecting the appropriate allegories from the Iconologia, by Cesare Ripa (1st edition Rome, 1593), and giving them a slightly new meaning in Judaic context.

(Ketubah Aharon Di Porto – Rosa Sessa, 12 October 1763 (5 Cheshvan 5524), Jewish Museum of Rome, gift of Clotilde Tagliacozzo in Piperno’s family, in memory of her father Angelo Tagliacozzo and of her mother Fortunata Di Porto, 2014 (Inv. 2368)

The deep association of the allegorical figures with Italian culture is expressed in another feature – rarely observed in the ketubot of other communities in Italy. Instead of using biblical verses, rabbinic concepts or Hebrew words, the allegories in Rome are often labeled by their familiar Italian name. Therefore, each is usually represented individually, set against a separate decorative background or frame, and the Italian word is inscribed below. As we may see in a ketubah preserved in the collection of the Jewish Museum of Rome, dated 1763, that features, in addition to two personifications of virtue, a third allegory, the central location and size of which imply it is the most important. It depicts not a single figure but a man and a woman with a golden chain encircling their necks with a pendant in the shape of a heart, which the two hold with their hands. The episode is entitled in Italian Concordia Maritale (“Harmony in Marriage”). This allegory is considered the ultimate representation of the perfect marriage, dominated by love and respect to each other. The chain, according to Ripa, is a symbol of the unification of the two, and that their marriage would never be dissolved unless one of them dies in the life- time of the spouse. Despite the Catholic overtones of this allegory (that is, it epitomizes the concept of the indissolubility of marriage in Christianity), this attractive image was found appropriate to decorate the Jewish marriage contract. In fact, it became the most popular allegory on Roman ketubot, appearing on numerous examples. Moreover, in nineteenth century specimens, the beloved image, by now a most familiar motif for the contemporary community, was “updated”: the man has a top hat, modern pants and a jacket, and the woman might wear a long fashionable dress, red shoes and a necklace (as in another ketubah of the Jewish Museum of Rome collection, dated 1817).

Some Roman ketubot exhibit also a rich biblical iconography – scenes that were carefully selected to fit Jewish ideas and ideals and at the same time show remarkable influence of Italian Baroque art. Often the biblical heroes and episodes appear in honor of the bridal couple who bear the same first names. Individual biblical miniatures for the bridal couple appears, for example, in the 1789 ketubah in the Roman Collection: Reuben handing the mandrakes (Mandragola or “love apples”) he picked to his mother, depicted in honor of Reuben, son of Joseph Menasci, the bridegroom, while the bottom episode, featuring King Ahasuerus handing the golden scepter to Esther in honors of Esther, daughter of Hananiah Sestieri.

The enrichment of the marriage contracts, even under changing circumstances, played a central role in the life of Roman Jewry, when Rome has become a true home for this beloved Jewish art form.

(Abstract and reworked from the essay by Shalom Sabar, Concordia Maritale. History and Art of the Ketubah in Rome, in O. Melasecchi – A. Spagnoletto, Antique Roman ketubot. The marriage contracts of the Jewish Community of Rome, Campisano Editore, Roma 2018.)