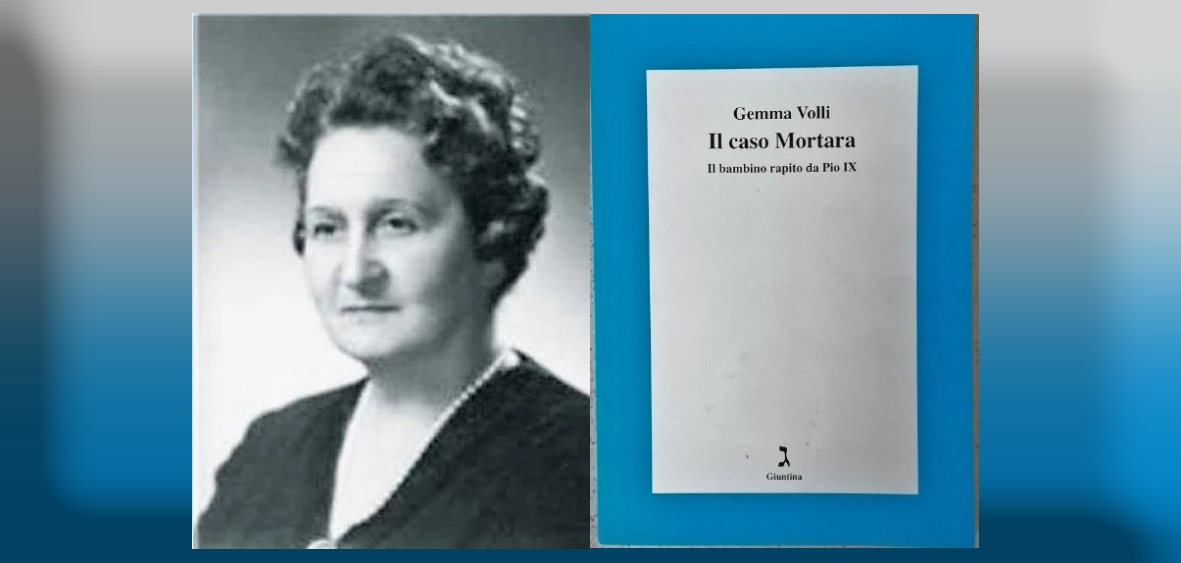

There is the Bologna of the Mortara family, a prisoner of hope, there is the Rome of the Pope, King for a little while yet, where converted Jewish children are forcibly “re-educated” into Christianity, against the background of a century of transition between the old regime and emancipation. Then the symbols, Jewish and Christian, which alternate on the screen in a struggle for identity, between those who are overwhelmed and want justice and those who see no salvation outside the church. And there is a Jewish boy: Edgardo.

Marco Bellocchio’s Rapito starts from there, from his focus on the child, imagining loneliness, darkness, despair and weaving a very powerful narrative on the story of Edgardo Mortara, baptized in secret and in 1858 taken from his family by the gendarmes of Pope Pius IX to be educated as a Christian. A dramatic action that becomes the driving force of a captivating film.

In the two hours of Rapito, in competition at the Cannes Film Festival, through the lens of someone who knows how to look beyond the thicket of sentences and interpretations of history Bellocchio restores the truth to a story that actually happened; he finds the points to synthesize, in such a complex, well documented story where the details are fundamental, to channel even the minor tributaries. “It is not an ideological film, nor a condemnation. – explains Bellocchio in conversation with Shalom – There was violence in this story, it’s obvious. Rapito tells of an actual happening”.

For a long time, Steven Spielberg thought about making a film about the story of Edgardo Mortara, then he gave up, and finally you did it. How did this decision come about?

The story of Edgardo Mortara has always fascinated me: the story of a kidnapped Jewish child, brought to Rome to be re-educated, because he had been baptized clandestinely, strikes the imagination. Edgardo’s change, the enforcement, the loneliness, darkness, accepting another religion in order to survive are aspects that attracted me, I didn’t imagine things like this could happen. For a long time I shelved the idea because I knew Steven Spielberg wanted to make a movie out of it, and when he gave up, I did it. Spielberg would surely have done it in English, but the truth must also be sought in language. The protagonists of this story speak Italian. There is Italy, our customs, the history of the country, Bologna, Rome, in short, a cultural territory in which we orient ourselves as best we can.

As a child you had a Catholic upbringing. How do you see Edgardo’s childhood?

When I was six I couldn’t have been all that different from Edgardo, even though I received a strict Catholic education. My human experience in the film refers to the child. However, it was essential to tell the life of the Mortara family and of how rooted it was in Judaism. We therefore consulted scholars and experts to represent Jewish rituals, prayers, habits and customs. We did it as best we could, because we felt it was an obligation for the artistic result and because, in cinematic terms, all this filled the scene emotionally.

In Rapito there is the almost constant presence of religious symbols. What weight and what meaning do they have?

They are very important. The symbols, such as the mezuzah, serve to outline and underline identities, to tell of the relationship of the Mortara family with Judaism. In the art of images, the symbol is not a piece of furniture, but has significant weight. In Rapito the mezuzah recurs, which is on the doorpost of the door of the Mortara house, and which Edgardo keeps with him even when he becomes a deacon.

Among the symbols is the crucifix, which appears to Edgardo in a dream. What did you intend to express with this dream representation?

The dream episode occurs after a crisis. For the first time after the kidnapping, in the house of the Catechumens, Edgardo meets his father and mother, who have been granted permission to see their son. The child tries to be obedient and to follow the directions given to him by the rector, but he can’t do it, he explodes in desperate tears because he has found his world and his mother again. When Edgardo is forcibly taken away from his mother and put back to bed, the dream becomes a child naivety wanting to reconcile his origins with the religion imposed on him. Then he removes the nails from the cross, freeing Jesus: for him it is like freeing himself and his people from the story of the accusation of deicide that was told him immediately after the kidnapping. It is a dream, a scene of reconciliation, in which Edgardo expresses the desire to find peace and see his parents again.

In the film, the narrative proceeds in a historically accurate fashion. A very particular scene is the one in which the representatives of the Jewish community go to Pius IX and ask for the return of Edgardo, a dialogue that seems to synthesize the harassment perpetrated by the Pope on the Jews. Was there awareness of this on your part?

It is an historically accurate scene. The Jews went to ask for benevolence, to be protected, because they were subjected to violence, even physical. The pope was particularly enraged because he suspected the Jews of trying to take back the child, so he threatened to put them back in the ghetto. And they, before leaving, as was the custom, kiss the pope’s slipper.

You depict Pope Pius IX as a complex figure: a ruthless man, at times a caricature. Why?

Edgardo’s kidnapping had an international echos in the United States and England. The newspapers published cartoons and caricatures of Pius IX in a sort of reverse shot of the whole world. One of these depicts the Pope’s hallucination of being circumcised by Jews who had penetrated the Vatican. We represent it in the form of a dream.

A dream that sums up the paranoia and centuries of stereotypes about the Jewish world…

The Pope reacted furiously also because he realized that his temporal power was collapsing. For the Italian Risorgimento, the Mortara case favoured the taking of Rome, it was its detonator.

The film gives much more importance to the international echo, less to the Italian one. And yet, Edgardo’s case makes all that noise because it took place in the middle of the Risorgimento and becomes its banner.

We made a choice, that of marking the international echo in order to synthesize. When you decide to tell such a vast and complex story in a film, you have to make many choices.

When the trial of Feletti, the inquisitor who had Edgardo kidnapped, took place in Bologna, we are already in the Kingdom of Italy. Here the film manages to tell, together with the human story, how the Mortara case was a weapon in the battle against the power of the Pope.

Yes, with a contradiction: Bologna is now Italian, but Feletti, the former inquisitor was acquitted because in his time the law in force, was the papal one. However, that trial remains a milestone because for the first time a member of the Holy Office ended up in the dock in Italy.

However, the parents were not interested in writing history, but in having their child back. The story of Edgardo Mortara has always represented a very deep wound in Jewish history, like the other cases of forced and clandestine baptisms. Do you think that your film can contribute to recounting that historical fact and making it known to the public?

We filmed with a good measure of freedom and with a healthy nonchalance. We have told this story not in an ideological way, not with the intention of showing all the injustices that the Jewish people have suffered, that is an implicit aspect of the story. The violent kidnapping of a child derived from a logic, the Pope acted consistently: if a child is a Christian because he has been baptized he must be Christianized, despite the violence of kidnapping. We don’t know, however, why Edgardo didn’t rebel during his lifetime.

mystery.