The epidemic of bubonic plague that struck northern Italy in 1630-1631 is known as one of the most violent of the modern age. It was Sukkot of the year 5391 when it hit the Jewish ghetto of Padua—one of Italy’s most ancient cities and the most ancient of all the Veneto region—and exacted a terrible toll from the Jewish community.

Preventive action was taken: halting all trade exchanges with the non-Jews, introducing social distancing in the three synagogues, hiring doctors to treat the sick at their homes, cleaning up the streets of the ghetto, bringing food and other supplies directly to the inhabitants. Yet all of that did not stop the plague from halving the population of the ghetto. At the onset of the epidemic 721 Jews lived in the ghetto. Of those, 421 died of the plague, 213 became ill and then recovered, and only 75 were never infected.

Nowadays we hear more and more about “resilience”, understood as people’s ability to deal with, and overcome, particularly difficult circumstances. What were, then, the proactive measures taken by Paduan Jews to counter the aggressiveness of the plague, the inadequate treatments available, the terror and sorrow of helplessly watching relatives and friends die day after day? What did they actually do?

Two leading factors brought about the end of the epidemic and halted Jewish deaths one full month earlier than in the rest of the city. The first was the decision to build a special lazaretto for Jewish patients only. The second was to use rented premises to disinfect all goods coming from the homes of the victims in the ghetto.

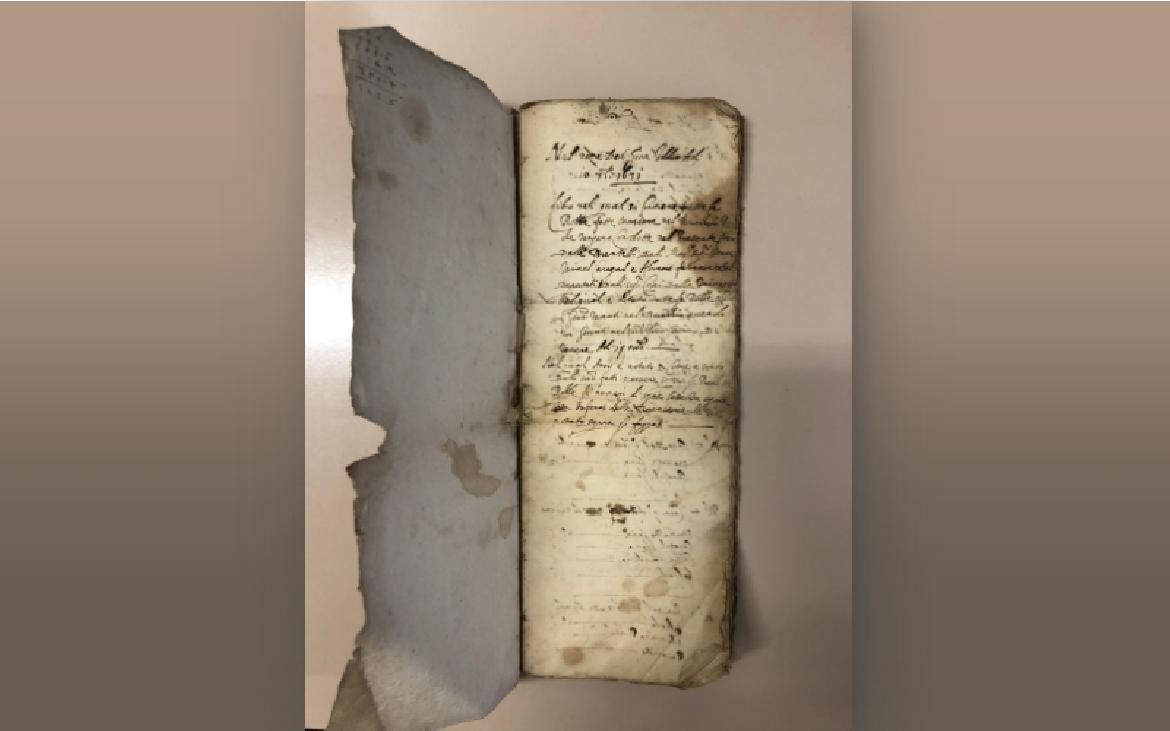

Rabbi Avraham Catalano wrote a very accurate chronicle of those events providing a wealth of details about every single aspect of those two terrible years. As far as we now know, his Libro de la peste che fu in Padova nel año 5391 (“Book of the plague that occurred in Padua in the year 5391”) is the world’s only Italian-language manuscript in the Olam Hafuch, the well-known Hebrew version of the famous journal of the plague in the ghetto.

In the summer of 1631, at the height of the epidemic, ghetto leaders were summoned by the superintendents (“Provveditori”) and governors (“Rettori”) of Padua, tasked by the Venice authorities with administering the city then under Venetian rule. Thus, they ordered the ghetto leaders to build a lazaretto out of town to take in all sick Jews, as they were not allowed into the Christian lazaretto, located near the Brentelle area.

At first, leaders of the Jewish Community were perplexed. Not only did the city authorities ask Jews to undertake the construction—they were also expected to bear its full cost. On this point, Catalano’s chronicle describes the bargaining that took place. Initially, the Provveditori and the Rettori were inflexible, but in the end they were persuaded to accept a compromise. After hearing from the Jewish leaders that in the Venice ghetto the Jews treated the sick directly in their homes, they allowed them to build the special lazaretto in the area of Porta Savonarola, not too far from the Padua ghetto. In turn, the heads of Padua’s Jewish community agreed to provide the lazaretto with every necessity, including beds, mattresses and bedclothes. Moreover, Catalano reported, they undertook the funding of the new hospital thanks to the generosity of Jewish community members, who donated foodstuffs on a weekly basis and funds to finance the building and to pay the doctors.

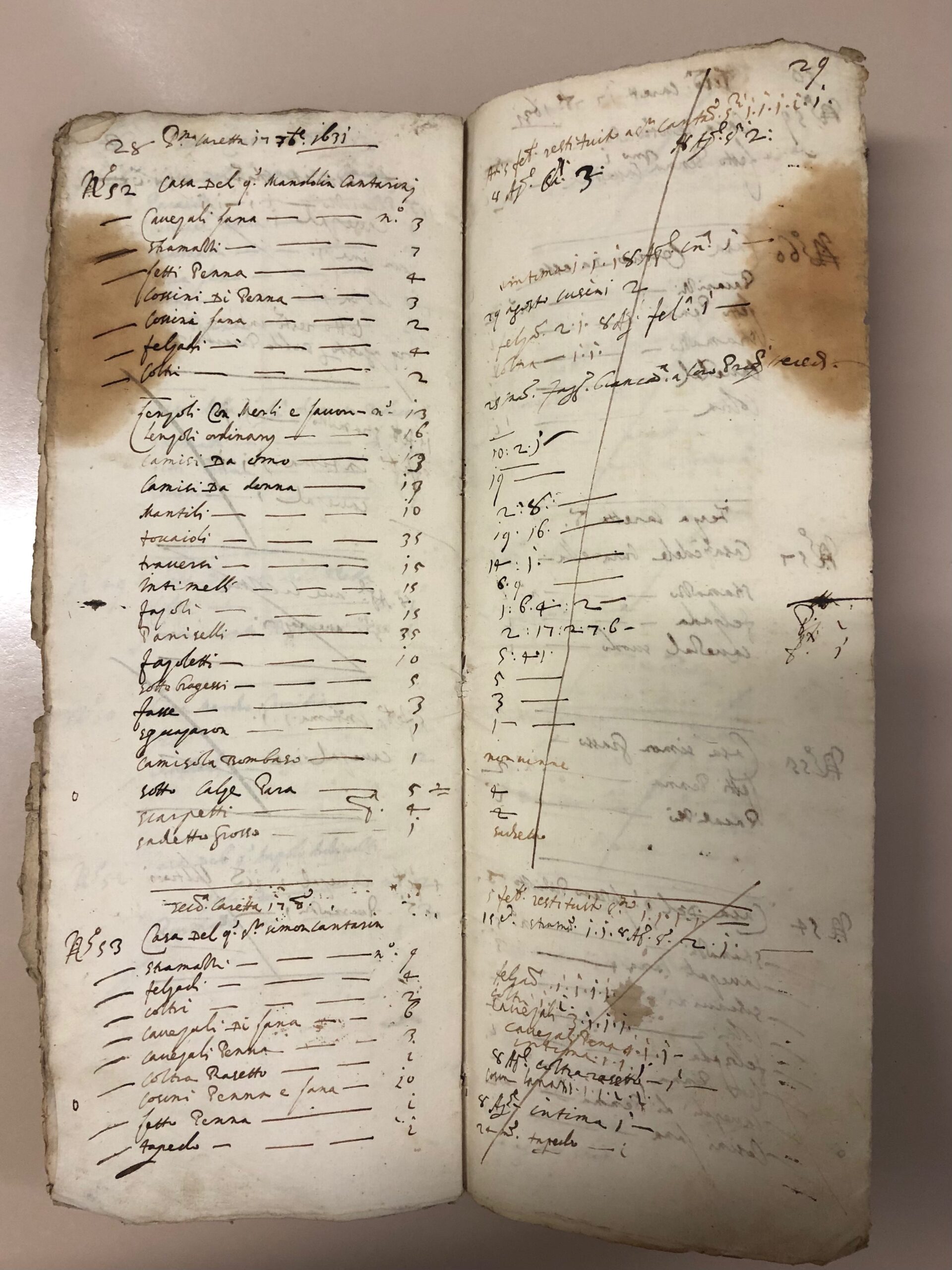

The Provveditore also ordered the Jewish community leaders to rent premises where goods from the homes of the plague victims would be disinfected. The community leaders took responsibility for sorting out items that could be disinfected from others—such as furniture, featherbeds and leather objects—that were later burned on bonfires lit on the city walls. Thus, by hiring trusted persons and paying them a daily salary, Paduan Jews took the final step out of the terrible plague.

All the measures undertaken were accurately recorded by Rabbi Catalano in his invaluable book—written in September 1631, as he himself states—that was recently found in the archives of the Jewish community of Padua. In the book we also read how new employees went from house to house, identifying the objects to be disinfected or burned, loading them onto special carts and then thoroughly cleaning all dwellings. Catalano’s chronicle even provides lists of all items sent to disinfection and returned months later to their owners.

Thus, although the epidemic was raging more violently than ever at that time, between late July and late August 1631 the numbers of infected ghetto dwellers decreased considerably, and deaths among Jews ceased completely towards the end of August.

This is how the Jews of the Padua ghetto joined together in those tragic circumstances and created the closely-knit network of solidarity, trust and cooperation that allowed them to emerge from the plague epidemic of 1630-1631.

Rebecca Locci attended Padua University of Padua, where in the academic year 2020-2021 she obtained her Masters Degree in Historical Sciences with a score of 110/110 cum laude by discussing her dissertation in History of the Republic of Venice, entitled The management of the plague in 1631 in the Jewish ghetto of Padua in Avraham Catalano’s chronicle.

(English translation by Marina Astrologo)